A review of Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields

As long as political ideologies seek to control the body and social lives of women, the personal will be political.

I sometimes think it’s a trite and outdated phrase and then Roe v. Wade is turned over in the US and Nova Scotia announces an epidemic of intimate partner violence, and I’m reminded that in fact, no, the personal, the body, it is still political because men think it ought to be. Women have never asked for powerful men to make our bodies the site of moral imperatives and political objectives, to wield our bodies as the softer weapons of war.

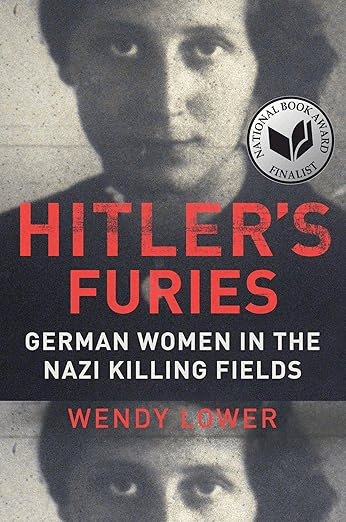

There is this idea that Nazism and Fascism uniquely appeals to men (there’s more Elon Musks than Laura Loomers in the world), and as a result, women were absent from the most terrible scenes of the crime (their domain children, kitchen, church), however we’ll learn how it was distorted and violent, all of it unbearably normalized, in Wendy Lower’s “Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields”.

Originally published in 2013, Lower’s book is the result of twenty years of painstaking research into archives (notably in the post-Soviet Eastern Front), witness statements, and investigative work. It is chilling in the amount of everyday death and brutality Lower has catalogued and the straightforward way in which she has presented it all. Some critics at the time noted she did not include accounts of professional killers, like those in the Reich Security Main Office or SS, as mentioned in the linked Guardian article. I can appreciate the sentiment, but I think it’s even more sinister to consider the unending ‘normal’ and brutal ways regular women were part of the regime – secretaries shuffling files that sent hundreds to the death squads, after work ‘shopping’ for a new pretty dress in the discards of victims from the gas chambers. I am a regular woman, living a fairly regular life. Most of us are ordinary people, living ordinary lives and relying on the system and world around us to keep functioning as we expect. Their system slowly sped its way into destruction, those in power made substantial legal changes that eroded the entire known word and as we experienced through the pandemic, people still had laundry and a job and meals to make. The every day necessaries continue to exist. That’s a more unsettling and universal story.

Wendy Lower first introduces the reader to what she calls the “lost generation”. Born in the tumult of Weimar Germany, with its blossoming civil rights, devastating economic and political turmoil and untold amounts of violence. There was as much promise, like Magnus Hirschfield’s Institute for Sexual Science and the women’s suffrage movement, as there was economic collapse and despair.

This generation of women, disillusioned and morally lost according to Lower were perfectly primed to be swept into the National Socialist movement. The first two chapters of “Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields” describes this environment and the perverse opportunity offered by the Nazis on the Eastern Front (as teachers, nurses and socials workers extolling Nazi “virtues”), notably once they’d made it impossible for women to find work they wanted.

The next three chapters describe the lives of six women sent to the Eastern Front and Lower ultimately divides the women between three categories: Witness, Accomplices, and Perpetrators. The most egregious actions were obviously taken by the perpetrators.

There is something to be said for the women like Annette and Ingelene Ivens who were “exceptional after the war” (Lower, 89) for the ways they spoke publicly what they saw. They didn’t hide away their involvement in family chests and seek to hide behind their femininity, like so many of the perpetrators. They didn’t go to the Stasi after the war ended and trade secrets for their freedom.

In the final chapter, “What Happened to Them?”, the answer is not much. White women, even women whose only power is the whiteness of their skin and their gender, have never been adequately punished for their murderous participation in things like the Third Reich or the murder of Emmett Till. The Guardian review accuses Lower of overselling her material, we know women can be violent and abusive, but we’re beyond it, and maybe that was the case in 2013, in the heady years of Obama, post-Sex in the City and Bridget Jones. But in 2024, 45% of white women voted for Trump. In his first days in office, he stripped away Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) programs that ensured employment for women and people of colour. Keep this in mind when you read chapter one of “Hitler’s Furies”. We’ve been seeing the rise of tradwife content which presents an idealized image of the mother who sacrifices all for the family. This idealized image, like that of Johanna Atvater in her crisp white apron, is a smokescreen. They don’t evolve much and only have one playbook.

Recommended to readers interested in women’s history, social history, World War II, German History and Fascism.

I borrowed “Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields” from my local library.

My recent reviews of women’s war experience can be found here: Devastating Minutiae in the Palestinian Experience: A Literary Review of Minor Detail

Review of a Poet’s Memoir: Looking at Women, Looking at War by Victoria Amelina

Did you know I’ve started publishing my own short fiction? You can find it over at Under the Poplar Tree on Substack. Be sure to subscribe, I publish a new short story every other Thursday.